Rapids: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "600px|right This page is for discussing the various rapids in Grand Canyon and how to navigate them. The first thing to remember in Grand Canyon is you have the ability to scout almost every rapid you will run, with few exceptions. The second thing to remember is everything changes! Water levels change throughout the day, changing available runs in the rapids. Side streams flash, rearranging the rocks in a rapid. When in doubt, stop, get...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Scouting_Upset.JPG|600px|right]] | [[Image:Scouting_Upset.JPG|600px|right]] | ||

The first thing to remember in Grand Canyon is you have the ability to scout almost every rapid you will run, with few exceptions. | The first thing to remember in Grand Canyon is you have the ability to scout almost every rapid you will run, with few exceptions. | ||

| Line 8: | Line 6: | ||

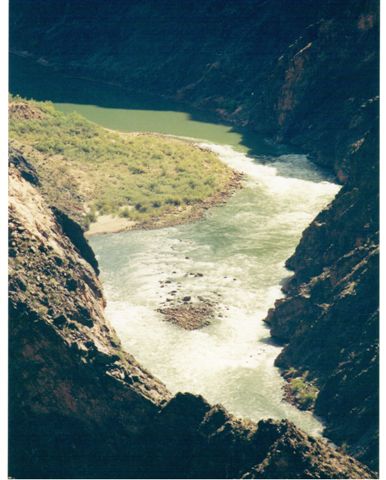

The photo on the right is of a river runner scouting Upset Rapid. Having a plan for what you expect to do in a rapid is a very good idea. | The photo on the right is of a river runner scouting Upset Rapid. Having a plan for what you expect to do in a rapid is a very good idea. | ||

The Grand Canyon is a pool drop type river. This means it generally has large rapids separated by stretches of flat water. The international whitewater scale rates rapids based on the amount of maneuvering that is required to negotiate the rapid and somewhat on the danger level. A class III rapid requires one maneuver to negotiate it. All the rapids in the Grand Canyon are class III or below with the exception of Hance which is long enough with multiple moves that earns it a class IV rating. Note that there really is little danger more than swimming and getting thrashed since generally a swimmer ends up in the pool below the rapid. But this scale does not capture the unique risks of flipping due to big water so the Grand Canyon uses a 1 - 10 scale. | |||

A common misconception is that it takes a lot of strength to row a raft through the Grand Canyon. In reality even the strongest person is not going to be able to match the strength of the river. Timing and using the river and momentum is much more important. Think about staying on your line through the rapid is more important than strength. | |||

A typical Grand Canyon rapid may involve a scout, then an upstream ferry to bring the raft across the river to where the tongue or route is located. Then it requires a pivot of the raft to face the bow into the rapid. A sideways raft is much more likely to flip and just straightening out will help your odds a lot. Typical rapids on other rivers (especially those with continuous rapids) would then require back rowing to slow the raft to allow time for maneuvering. The rapids in the Grand Canyon are different as doing this in large waves can cause the raft to flip. So entering the rapid you want to be pushing on your oars to get a little more momentum to punch the waves and holes. | |||

For large waves and holes momentum helps but timing is more important. For a kayaker hitting that wave or hole and reaching over it to the downstream water with your paddle not only pulls you through but provides a great deal of stability. So instead of thinking of one last strong stoke before the wave or hole think about timing to get that downstream water as quick as possible. For a raft the sweep of the oars is quite long so it is likely the blades are outside of the wave or hole. But the idea is the same to grab downstream water as soon as possible. Sometimes this may be above the wave or hole to help punch it and sometimes it will be to the side or downstream. This is not so much a rowing stroke as planting the blades like anchors with a slow stroke and using your weight to hold the blades and then your muscles. Basically you are pitting the downstream water against what you want to punch and letting them fight each other instead of trying to fight the river. Although you are in the middle of these forces you can give a bit during the worst part. Leaning on your oars and using your weight also automatically provides some high siding which helps to avoid a flip. | |||

Often to get out of the tail waves and maybe some worse stuff mixed in it is necessary to turn the raft somewhat sideways before rowing. Timing is critical when turning in the middle of a rapid. Rowing an 18 foot heavy gear boat and trying to turn when the raft is in a trough and the bow and stern are buried in waves is futile. But reaching the top of a wave, getting the blades into some water and spinning with the bow and stern completely free of the river is fairly easy. | |||

In kayaks and canoes it is easy to be intimidated by the large waves and lean away from them. This just makes a flip more likely. Just like leaning forward on your oars, in a kayak or canoe it is important to attack the waves and lean forward. This also makes it easier to reach for that downstream water. | |||

Revision as of 09:48, 11 May 2024

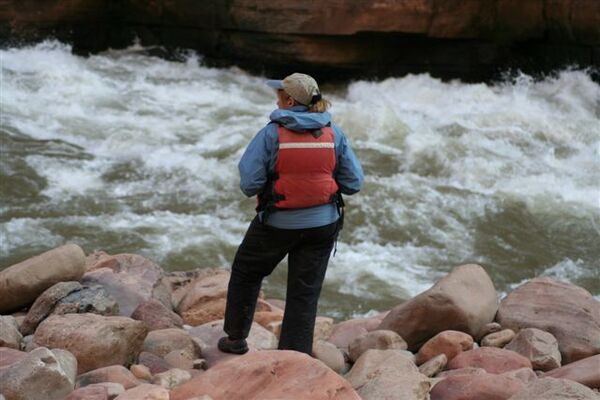

The first thing to remember in Grand Canyon is you have the ability to scout almost every rapid you will run, with few exceptions.

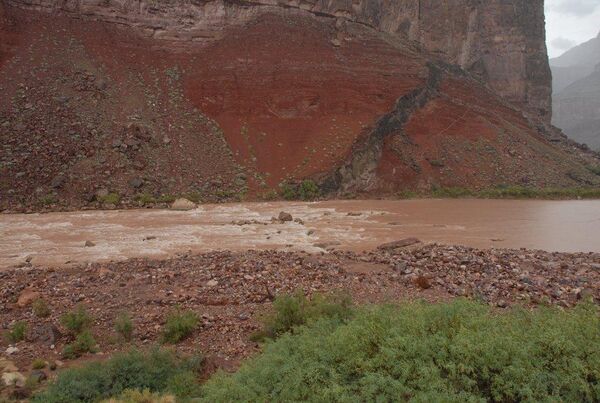

The second thing to remember is everything changes! Water levels change throughout the day, changing available runs in the rapids. Side streams flash, rearranging the rocks in a rapid. When in doubt, stop, get out of your boat, and scout it out!

The photo on the right is of a river runner scouting Upset Rapid. Having a plan for what you expect to do in a rapid is a very good idea.

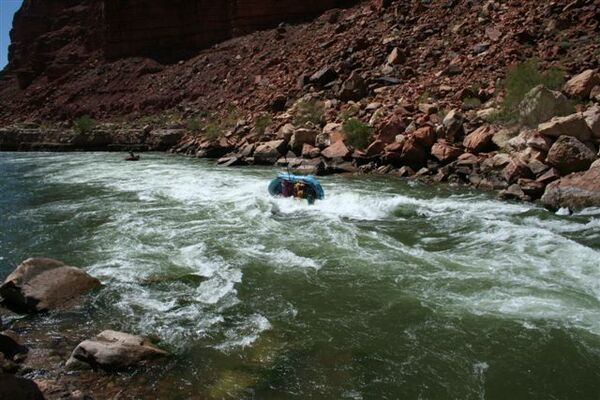

The Grand Canyon is a pool drop type river. This means it generally has large rapids separated by stretches of flat water. The international whitewater scale rates rapids based on the amount of maneuvering that is required to negotiate the rapid and somewhat on the danger level. A class III rapid requires one maneuver to negotiate it. All the rapids in the Grand Canyon are class III or below with the exception of Hance which is long enough with multiple moves that earns it a class IV rating. Note that there really is little danger more than swimming and getting thrashed since generally a swimmer ends up in the pool below the rapid. But this scale does not capture the unique risks of flipping due to big water so the Grand Canyon uses a 1 - 10 scale.

A common misconception is that it takes a lot of strength to row a raft through the Grand Canyon. In reality even the strongest person is not going to be able to match the strength of the river. Timing and using the river and momentum is much more important. Think about staying on your line through the rapid is more important than strength.

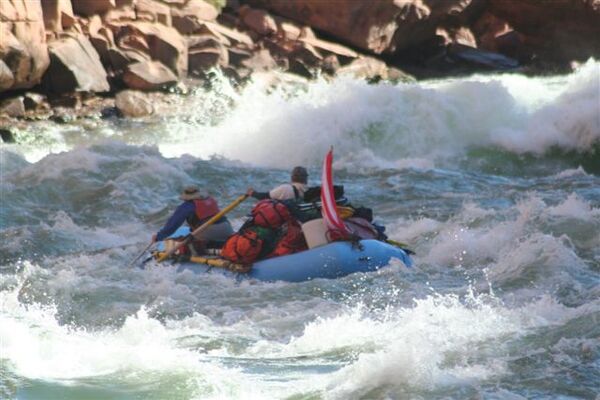

A typical Grand Canyon rapid may involve a scout, then an upstream ferry to bring the raft across the river to where the tongue or route is located. Then it requires a pivot of the raft to face the bow into the rapid. A sideways raft is much more likely to flip and just straightening out will help your odds a lot. Typical rapids on other rivers (especially those with continuous rapids) would then require back rowing to slow the raft to allow time for maneuvering. The rapids in the Grand Canyon are different as doing this in large waves can cause the raft to flip. So entering the rapid you want to be pushing on your oars to get a little more momentum to punch the waves and holes.

For large waves and holes momentum helps but timing is more important. For a kayaker hitting that wave or hole and reaching over it to the downstream water with your paddle not only pulls you through but provides a great deal of stability. So instead of thinking of one last strong stoke before the wave or hole think about timing to get that downstream water as quick as possible. For a raft the sweep of the oars is quite long so it is likely the blades are outside of the wave or hole. But the idea is the same to grab downstream water as soon as possible. Sometimes this may be above the wave or hole to help punch it and sometimes it will be to the side or downstream. This is not so much a rowing stroke as planting the blades like anchors with a slow stroke and using your weight to hold the blades and then your muscles. Basically you are pitting the downstream water against what you want to punch and letting them fight each other instead of trying to fight the river. Although you are in the middle of these forces you can give a bit during the worst part. Leaning on your oars and using your weight also automatically provides some high siding which helps to avoid a flip.

Often to get out of the tail waves and maybe some worse stuff mixed in it is necessary to turn the raft somewhat sideways before rowing. Timing is critical when turning in the middle of a rapid. Rowing an 18 foot heavy gear boat and trying to turn when the raft is in a trough and the bow and stern are buried in waves is futile. But reaching the top of a wave, getting the blades into some water and spinning with the bow and stern completely free of the river is fairly easy.

In kayaks and canoes it is easy to be intimidated by the large waves and lean away from them. This just makes a flip more likely. Just like leaning forward on your oars, in a kayak or canoe it is important to attack the waves and lean forward. This also makes it easier to reach for that downstream water.

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, here are some videos to show the real things. PLEASE NOTE: Links to videos change often. If you find a broken link, click here to let someone know. Thanks!

Duwain Whitis has put together a video titled Carnage at Lava Falls. See if you can see how you might run that rapid differently, given a chance. Thanks to Duwain for putting this video together.

Here's a fantastic YouTube video from April 2008, showing a flip in Lava Falls Rapid. Can you see why this river runner flipped? The saying "hit um straight" was not applied here.

Here's another YouTube video from April of 2008, of an teenny weeny boat taking on Hermit. The rapid wins. This video is a good one to show the rapid.

Resources for rapid information are the Facebook Groups Rafting Grand Canyon and Green and Colorado River Rafters Paddlers Sups and Swimmers where you can share information with river runners with a wealth of Grand Canyon experience, including discuss rapids. The Rafting Grand Canyon group is at [1]. The Green and Colorado River Rafters Paddlers Sups and Swimmers group is at [2].

River runner Jim Michaud has put together a How-To-Row-The-Grand-Canyon-Rapids guide for river runners. You can download the 2020 updated pdf document here.

River runner Marc Hunt put together a 2 hour video on the Grand Canyon rapids. It's worth a watch and is here.

Finally, there are a lot of scary rapid videos out there. Most river trips do not have a flip, so you won't do yourself any favors by getting all worked up about this. K?

Ok, so let's look at some specific rapids. Remember, scout it out, and things change!

Speaking of Change, Soap Creek Rapid changed in August of 2015 after some serious monsoon rainstorm activity. You can see a few videos of the rapid taken September 6, 2015 at these Vimeo links:

Additional information about this rapid and the recent change can be found here.

House Rock Rapid at river mile 17.1 is a rapid worth the scout. The run is a cross river ferry to the right, moving to river right to bypass a large hole on river left. If you scout this rapid on the left, you exit the shore going right. If you scout from the right, you must exit the shore pulling upstream to river left, then turn and start pulling to river right. Given that info, you might want to consider scouting this one on the left.

So, what about that sleeper rapid? How about something simple like Twenty Three Mile (Indian Dick) Rapid. Check out this photo of a 16 ft self-bailer doing the side roll flip in Indian Dick. Note the easy left run. It's possible this flip could have been avoided if the rapid had been scouted.

Here's a photo of river runners on a boulder near the river right shore at an unnamed riffle at river mile 56.7 just below Kwagunt Rapid. This boat was close enough to shore that a throw-rope thrown from shore allowed a static line to be set to the boat and a shore based Z-drag set up pulled the boat off the boulder. This non-self bailing boat sustained only minor damage (one bent spare oar) and the boats floor had no leaks after it was recovered! The moral of this story is to pay attention at all times.

Here's a bird's eye view of 75 Mile Rapid. To avoid the holes down the middle and on the right, one can go down the left side with a downstream ferry to the left at the top. There are holes all through this rapid, but by looking downstream and identifying hazards ahead of time, you can miss them.

Things change. Slowly and sometimes, quickly. On the right is a photo of Hance Rapid from March, 2012. The left run was between the big "Muffin" (also called the Brain or Hamburger) rock and the left shore. The summer monsoons of 2012 brought a wall of boulders into the left side of the rapid, and this left run is now closed (below).

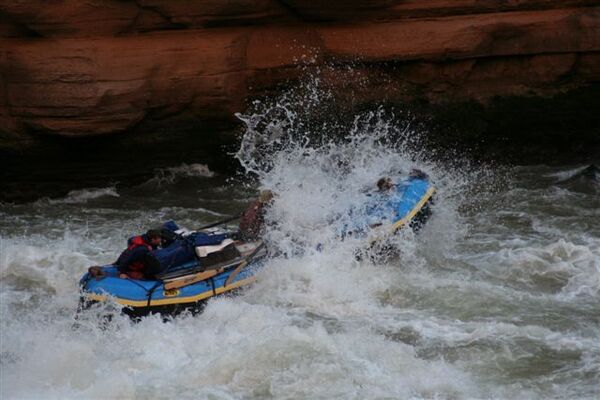

Here's a series of five photos taken from shore of a Western River Expeditions motorized raft hitting the big wave in Hermit August 6, 2010. One passenger was forcibly thrown from the raft, while another sustained a compound arm fracture. Bystanders on shore noted the motorized boat was at full speed entering the hole and that there was plenty of room to miss this hole on either side, or go slower. The fifth photo shows feet in the air.

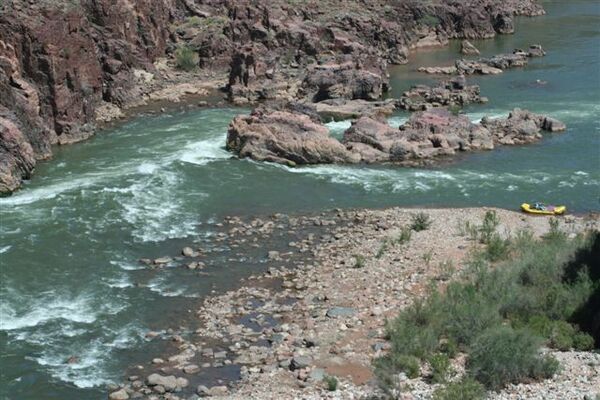

Here's an upstream view of Crystal Rapid at river mile 98.8. Sometimes you will need to think about what's immediately downstream of the rapid you are running. As this photo shows, if you run right in Crystal, try to stay way right. If you go left in Crystal, try to stay way left. If you end up in the middle of the river in Crystal, beware the Rock Garden, clearly seen in this photo. The big boulder in this photo of the Rock Garden is called "Big Red". Go right or left, but don't attempt to go right down the middle.

The same two boat Western River Expeditions motor trip shown at Hermit Rapid above, ran their other motor boat onto the Crystal Rock Garden. The boat had not been there 24 hours pinned on Big Red, when another concessions river trip, Outdoors Unlimited (OU), running a twenty foot long yellow baggage boat, ran into the Western boat stuck in the Crystal Rock Garden. The yellow and black blob is OU's gear boat.(Photo courtesy NPS and M Young)

Here's a view of Bedrock Rapid at 131 mile, as seen from about a quarter mile upstream. The flow is low, maybe 7,000cfs. Note the rocks on river right. The run on this day was just left of the right shore rocks, then a pull into the right channel. That run works at higher water levels too. You really don't want to go left at Bedrock.

There were three gents in this boat at the start of this Bedrock run. Not making the right cut, the boat rolls steeply in the hole/eddy fence at the top of the left run. One swimmer is quickly flushed out, as is the boat and now two passengers, luckily for them right side up!

Here is a good left run at Upset Rapid at river mile 150.2. If you try the right run at Upset, stay Right! If you go left, stay left, but don't go into the left run too high and too fast! You might just hit the left wall and flip at the top of the rapid.

What about Lava Falls?

Here is a video of a good run through Lava Falls in a replica of a 1957 Grand Canyon Dory, with Hazel Clark fish-eyeing in the front. This is the classic low water run on the right.

Here's a photo of Pearce Ferry Rapid from August 17, 2010. This rapid is located at about river mile 280.8. For the second half of 2012 through July 2013, this rapid was runable again. You will encounter this rapid after about 30 miles of fast moving flat water. Scouting is recommended on river left if you do not take out at the Pearce Ferry Ramp just upstream of this rapid. More photos of this rapid are at the River Runners For Wilderness photo gallery. In 2015, running this rapid is not recommended. A hard portage on the right is an option.

For an interesting read of what rafting Grand Canyon in high water is like, you may enjoy reading the 1983 High Water Trip Report by Chuck Zemach page.

Click here to return to The Trip page.

Did you find this all volunteer-built WIKI helpful? You can express your appreciation with a donation to the non-profit River Runners for Wilderness here! Thank you!